I don’t expect to find many spiders in Pittsburgh during February, but right in front of me in the middle of a snowy trail I found a ghost spider. Ghost spiders are harmless, roaming hunters that are most often found on vegetation. Their average size is 3 – 8.5 mm depending on species. They are pale yellow with spots and flecks of brown. Ghost spiders are in the Anyphaenae family with thirty eight species found north of Mexico.

Ghost spider in the Hibana genus.

Ghost spider in the Hibana genus.

Ghost spiders do not use silk to trap prey. Instead, they actively hunt, mostly at night, among the foliage of trees and shrubs. Head out with a flashlight in the summer and poke around the leaves of a young maple tree and you’ll probably just catch a glimpse of one. They are fast moving and can “stick” to surfaces using specialized claw tufts. The hairs on the claw tufts are called lamelliform setae which translates into hairs that are scale-like or plate-like. These setae basically give the spider more points of contact with the surface allowing them to disappear to the underside of a leaf with ghostly quickness. They are hard to catch.

Spider “paws” of a ghost spider.

In the cold temperature ~35 degrees, the spider was moving slowly and it was conspicuous against the whiteness of the snow – bird food waiting to happen! I gathered up the spider to take home for observation. I thought I had slightly interrupted the food chain, but it turns out this spider was already a firm link in that chain.

My initial exam of the specimen under the scope revealed that it was an immature spider – I couldn’t see an epigynum (hard, cuticular plate that is the female’s reproductive opening on the underside of the abdomen) and the spider didn’t have swollen palps (indicating a male).

Possibly an immature female. The two pale patches you see are the spider’s book lungs.

A mature female with an obvious epigynum between the book lungs.

Immature male ghost spider with swollen, palps for comparison.

This is where the story gets very interesting! Did you notice the tiny bug attached to the spider’s pedicel in the first photo above? The pedicel is the official word for a spider’s “waist”. Let me zoom in…

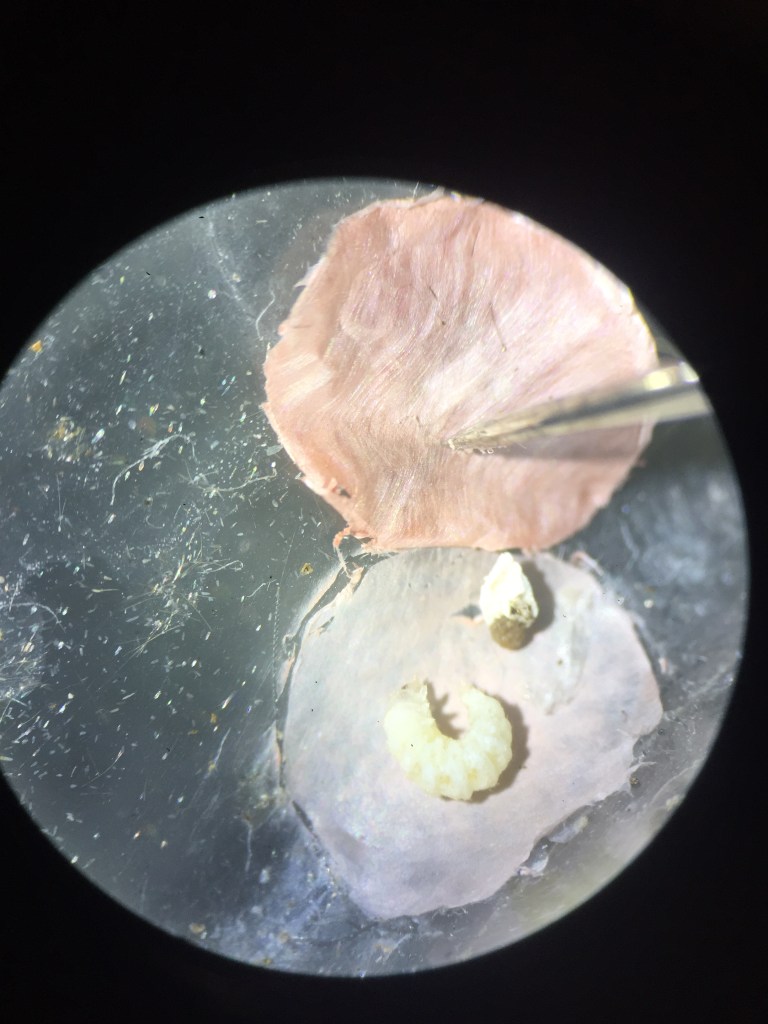

It was a spider parasite! I’ve seen spider parasites before, but they’ve all been some type of wasp larva which looks like a tiny little maggot attached to the abdomen of spiders. This one was different with six well-developed legs, something that wasp larvae don’t have. And it was really small, less than 1 mm. It was definitely an insect (as opposed to a mite), but I was stumped beyond that.

A typical grub-like larval stage of what is most likely a wasp attached to the abdomen of a spider. The larva eats the spider alive.

Close up of what I pulled off of the ghost spider – 1 mm long, tops!

I decided to perform a micro “parasitedectomy”. Having successfully plucked wasp larvae off of delicate spider abdomens, I figured it would be a similar process. The trick was keeping an active ghost spider still during the process which is where CO2 comes in. CO2 used for spraying dust out of electronics can also be used to anesthetize spiders. I put the spider in a small vial, gently sprayed in the CO2 and sealed the lid. In moments, the spider was motionless, but I only had about 5 minutes to perform this delicate task!

Using the dissecting scope, fine forceps, and a needle to maneuver and grip, I think I held my breath the entire time! Interestingly, the CO2 knocked out the spider, but not the insect! The insect remained mobile, squirming a bit in reaction to being prodded. It took a steady hand and very gentle strokes but it worked! The spider “woke up” a few minutes later and was fine and free of its hitchiker. The parasitedectomy was a success and I was able to get better photos!

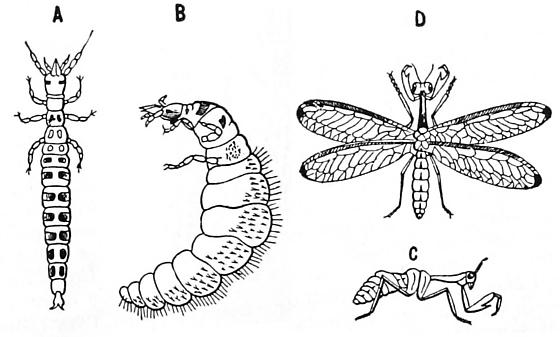

After I reached out to more knowledgeable people on the subject (thanks, Sarah!), I found out that this leggy parasite was a mantisfly larva. Mantisflies are the perfect misnomer. Although they have raptorial forelegs and heads like mantids, they are not mantids. Nor, are they flies (as in our familiar horse and bottle flies). They belong to the Neuroptera order of insects commonly called lacewings. Here is a photo from Bugguide.net showing the small size of the mantisfly. They are a little over an inch long, not as big as the true mantids.

The life cycle of a mantisfly is really interesting. Members of the Neuroptera sub family Mantispinae are major spider predators. Crawling onto a spider is merely a way to get to the real prize – the spider’s eggs.

The adult mantisfly will lay hundreds of long, oval-shaped eggs each attached to a surface by stalks. When the eggs hatch, the larvae are in a crawling phase (A in illustration above). In the paper, The Biology of the Mantispinae, Redborg mentions that the larvae most likely wait around with legs raised for a roaming spider to pass over them and then the larvae latch on and crawl up the spider’s leg – kind of like how a tick hangs out on the edge of a twig waiting for a mammal to brush by. The goal is to burrow into the egg sac so that the fly can finish its metamorphosis. Once the mantisfly finds an egg sac (usually a personal haven, one sac per mantisfly larva) it changes into a more grub-like form (B) better equipped for laying around and eating rather than moving. When the mantisfly has had its fill of spider eggs (sometimes all of them, sometimes not), the larva builds a cocoon inside the sac and goes into a pupal phase (C). This type of metamorphosis, with distinct larval phases, is called hypermetamorphosis and is atypical for insects; only a few kinds go this route. The adult mantisfly (D) continues the cycle mating and laying eggs leaving the spider hunting to the larvae.

Within the Mantispinae genus, there are some mantisflies that absolutely need to be ON a spider first, called “boarding” to successfully carry out their life cycle. Some mantisflies don’t board at all, but penetrate an egg sac once it’s already been made. I guess they find an egg sac by chance. Finally, there are some mantisflies that can go either way.

The spider I caught wasn’t mature – not ready to mate and weeks away from doing anything about an egg sac. And what if this spider was a male? DOH! Well, mantisflies can wait it out and will survive on their spider vehicle by finding a soft crease in the spiders cuticle, attaching with their piercing mouth parts, and feeding on the spider’s blood. Some of these soft areas are IN spider’s book lungs, near the base of the legs, around the cheliceral area, and wrapped around the pedicel – places where the spider cannot groom them off. These are also places where the fly can stay put when the spider molts to maturity. If the mantisfly happens to crawl onto a female, that’s a bonus! The fly just needs to wait around for the spider to start laying down the silk layers for an egg sac and the fly simply gets woven in. If the mantisfly has boarded a male spider, the fly can transfer to the female during spider mating or other close contact encounters such as spiders eating spiders.

In a study by Hoffman and Brushwein, they found that of all the spiders they collected as mantisfly hosts, Ghost spiders were the most common with Sac spiders and Jumping spiders following in popularity. They noted that these types of spiders don’t make capture webs but do make silken retreats where they molt or hide when they’re not hunting. Maybe the mobile fly larvae detect these hide outs and ambush the spiders! It was also noted that Mantisfly larvae have been found on web-building spiders, but not nearly as often.

Now that I’ve learned all of this, I wonder if the weird little grub I found in a spider egg sac last year was a mantisfly larva. I caught the spider in August of 2020 on the backyard compost bin (Pittsburgh). It was a mature female in the Phrurolithidae family (Bugguide nicknamed this family “guardstone spiders). It died soon after making its red, disc-shaped sac. I waited and waited for the spiderlings to emerge. I thought the eggs were infertile. I opened the sac out of curiosity and found this:

Mantisfly larva?

Very pretty mature female spider from the Phrurolithidae fam.

What’s left of the eggs is in the upper right. They were a dried lump. I looked back at my photos of the spider – no obvious sign of the 1st instar mantisfly anywhere on the spider. Maybe it was in the spider’s book lungs? Referring to the paper by Redborg, he hypothesized that if a larva was hiding in a spider’s book lungs, it would be a smart move to crawl to the pedicel where it’d be closer the the egg laying when the time came. So where’d it come from? I’m not positive that the above larva is a mantisfly, but it sure seems to fit the bill!

Spiders not only play an important role as a predator but also as prey for many animals, the mantisfly being one of the more interesting spider hunters. If I had left the ghost spider on the trail with its hitchhiking larva, a bird could’ve ended everything in one boring gulp! I’m glad I found the ghost in the chain to reveal what’s not so easily seen!

The Mantispidae (Insecta: Neuroptera) of Canada, with notes on morphology, ecology, and distributionBy Cannings R.A., Cannings S.G.

Can. Entomologist 138: 531-544, 2006

Redborg, Kurt E. 1998. Biology of the Mantispidae. Annual Rev. Entomol. 34:175-94.

Hoffman, KM, Brushwein JR, 1989. Species of spiders (Araneae) associated with the immature stages of Mantispa pulchella (Neuroptera: Mantispidae). J. Arachnol, 17:7-14.

Wow, another really interesting post. The only mantispids I’ve ever seen were those found emerging from egg cases of Argiope keyserligi in Australia. Your post was a great education for me. I had heard about the biology of mantispids, but since I’d not seen them (with that sole Australian exception) it had faded in my memory. Great photos too!

LikeLike

Yay! Thank you!! I’ve never seen the eggs or an adult in person. Now I’ll be looking!

LikeLike

Hi Amy,Found this little one on my friend’s car today. Can’t find it in Bradley’s book. Got any ideas?Frances

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

LikeLike

Maybe Eris militaris?

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

LikeLike

Amy,

For some reason known only to the cyber deity, I see no photo for Frances’ comment. Maybe you could see if you can download it and send it to me?

Rich

Richard Bradley, PhD Associate Professor Emeritus Acarology Laboratory, Room 1380f EEO Biology, 1315 Kinnear Rd The Ohio State University Columbus, OH, 43212 work: (614)292-7180 home: (740)363-4239 http://spidersinohio.net bradley.10@osu.edu National Academy’s statement: http://www.nas.edu/evolution/ Pronouns: he/him/his Honorific: Dr.

________________________________

LikeLike

I can’t see a photo either…waiting for Frances to reply!

LikeLike

Hey Frances! I don’t see a pic. Can you email it to me (Spidermentor@gmail.com) and Cc Dr. Bradley?(mailto:bradley.10@osu.edu)

LikeLike