How exciting! If you’re reading this I guess it worked!

This post goes out to anyone who has seen this scary headline in its many shapes and forms about the introduced Joro spider (Trichonephila clavata).

If you clicked these colorfully titled articles because it freaked you out, then you fell for it hook, line, and sinker. It’s a SCARE tactic. The more clicks these horror movie-titled articles get, the more they get shared, perpetuating the spread of negative associations with spiders. Headlines like this keep stoking the fire (“burn the hahse dahn!”) that spiders are inherently dangerous, which isn’t true. Unfortunately, most articles and news reports make spiders out to be GROSS, TERRIFYING, and DISGUSTING. Even some older children’s books cater to this idea that spiders should be feared.

I can assure you, there will not be giant, flying spiders landing on your heads and injecting venom the instant they make contact. If you take away the sensationalism, this is simply a case of a potentially invasive orb-weaving spider that has been introduced by people. Yay us! Instead of being terrified, we need to be observant.

When Joro Spiders “Landed”

The first Joro spiders in the US were spotted in 2014 and professionally identified in Madison County, Georgia most likely introduced there in a shipment from the spider’s native stomping grounds, Eastern Asia. That’s ten years ago (as of this writing), a long time for an “invasion”, in my opinion. The scary articles are trying really hard to shock you with warnings that these spiders are flying in swarms, like you’re gonna look up in the sky and see a dark cloud approaching from the south. Spiders do not have wings and never will. “Ballooning” is the proper term, a common spider behavior, but only the tiny spiderlings can do it. Ballooning is used as a dispersal method when the cluster of sibling spiderlings (sometimes hundreds) need to get away from each other before cannibalism occurs. They’ll climb to the tip of a branch, raise up their little butts and shoot out a wispy strand of silk in hopes that a breeze will carry them to a nice spot where they can live independently and fend for themselves. They have no control over where they’ll land. Intentional “flying” is not what’s happening.

VENOMOUS!

What about the venom?? Saying “venomous spider” is kind of redundant. Yes, Joro spiders ARE venomous. ALL spiders, except for a few oddball types, have venom glands and therefore, have a venomous bite. Venom helps spiders subdue prey which are usually well-armored arthropods that will put up a pretty good fight. Spiders also inject venom to start the digestion process, liquefying the hard parts since they can’t chew their food. The emphasis on VENOMOUS in most of the scary article titles are meant to concern you so you continue to read. Usually, somewhere in the article, it’s admitted that the Joro spider’s venom is not medically significant to humans. In other words, unless you’re a flying insect, they’re totally harmless. I hope that’s not too disappointing, I mean, what good is a horror movie if the bad guy is really chill and not interested in anything but grasshoppers?

Similar situation

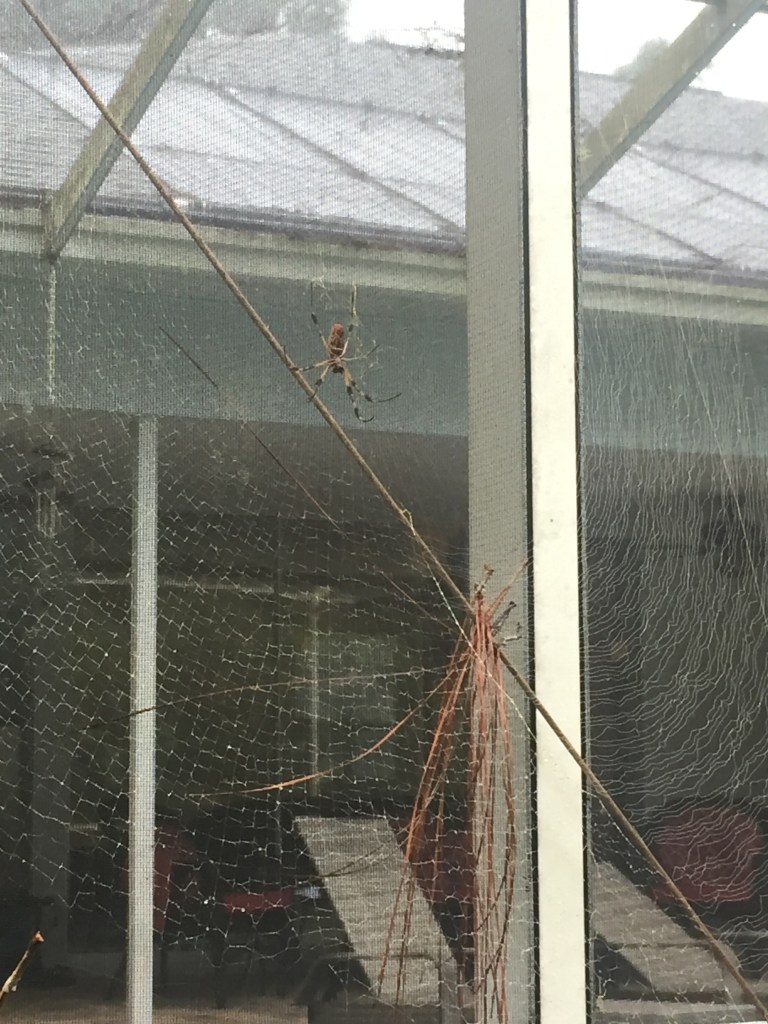

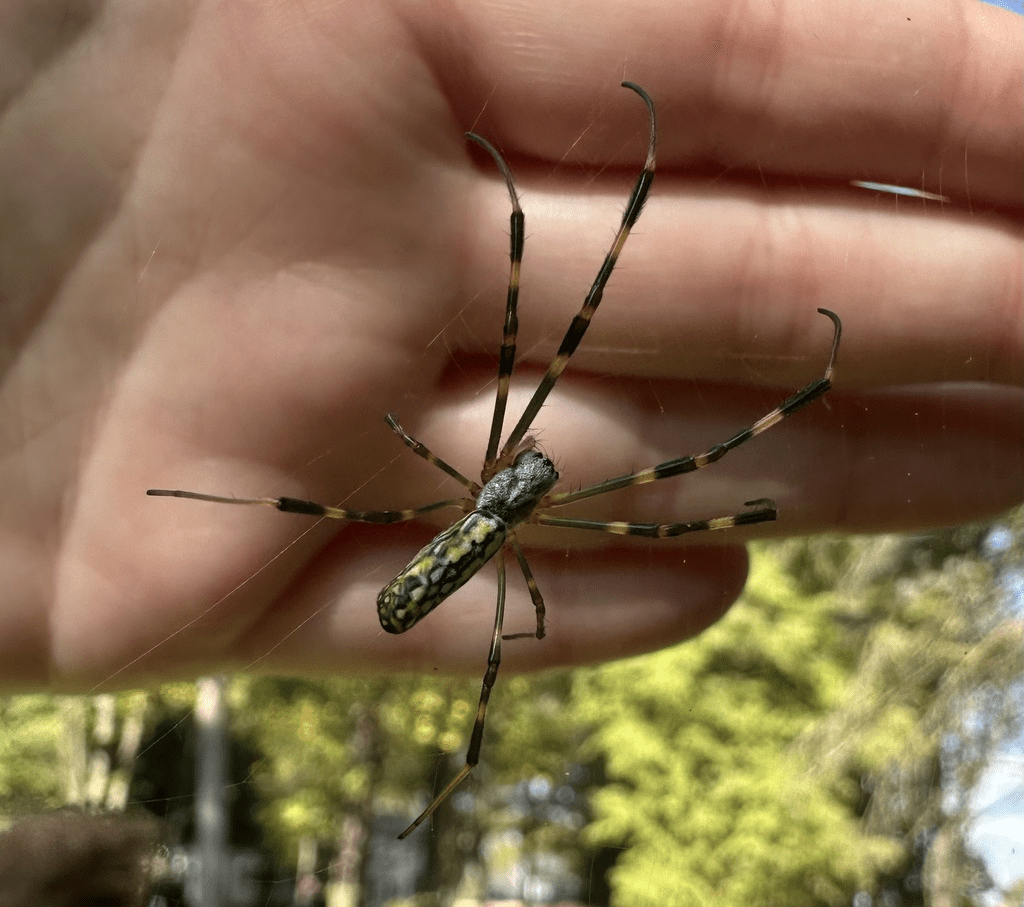

I never met a Joro spider in person, but according to some of the articles about them, Pittsburgh should be shrouded in silk with a web adorning every light post. This hasn’t happened. In the meantime, we can admire the Joro’s east coast relative. Have yinz guys ever gone down south and seen the giant orb webs of the Golden Silk Orb Weaver (Trichonephila clavipes)? They’re numerous and not easy to miss. Any walk along a pine needled path will reveal web after web among the branches. The silk reflects golden and the large spiders grip the fine threads with tiny claws on the ends of their long, thin, tufted legs. They’re big, beautiful spiders, rusty orange with white spots. The leg span is what makes them large, but they’re not heavy-bodied like a tarantula by any means. Guess what? The Golden Silk orb weavers are actually larger than the “giant” Joro spider. In addition to the two spiders being closely related, Golden Silk orb weavers were also introduced into the United States somewhere around 1865. They quietly established themselves in our warmer southern states without causing any widespread panic. No swarm. No wings. No venomous attacks on the helpless, horrified townspeople.

Sensationalizing the research

What I found to be most misleading in the “GIANT, FLYING, VENOMOUS” articles I read was the suggestion that we should be “bracing for the east coast surge of the flying spider army” as if the spiders are marching in droves to come eat us. Once you click and start reading, the threats begin to backstep when the experts are featured. The stories are based on real research, but with a creative interpretation of the study results to make it sound like something awful and dangerous is going to happen and there’s nothing we can do about it.

In a 2024 publication, Joseph Giulian, et al, used species distribution models to forecast the potential range of the Joro spider. Species distribution models are predictive. They are based on annual mean temperatures around the globe and were compared with the climates where Joro spiders actually live, climates where they’ve been found outside of their native areas, and other existing data. The take away from the study was that there are very possible, suitable habitats for Joro spiders along our east coast, further north than the Golden silk orb weaver cousins could survive. Lab tests showed that the Joro spider can tolerate and survive colder temperatures. The species distribution models are based on potentialities, so we still don’t have a grasp on how well Joro spiders might actually survive our winters if they do get here. Another unknown is how our native spider predators will react to a possible new menu item.

How far they’ve advanced

Since the initial sighting of the Joro spider in Madison County, Georgia, biologists and community scientists have been tracking them. There is an online JORO WATCH via the University of Georgia and, of course, iNaturalist is keeping tabs. Most of the documented Joro spiders are primarily scattered around the site of establishment in Georgia. The Joro spider has definitely settled in and is successfully breeding in that surrounding area. A paper by Robert Pemberton published on April 23, 2025 states, “The Joro spider and the native orbweavers were censused in 25 forests in the Atlanta [Georgia] region from 2022 through 2024. The Joro was found in all 25 sites in all three years, doubling in abundance each year” (Pemberton, 2025). It’s clear that this spider is invasive in Georgia since Pemberton also documents that the native orbweaver counts have gone down in relation to the rise of the Joro spider population.

Going north, in fall of 2024, there were two confirmed Joro sightings in York, Pennsylvania and two in Suffolk County, Massachusetts (our most northern sighting yet) which ignited another round of horror movie-like headlines that the east coast was “under attack”. The spiders found in Pennsylvania were both immature. I wonder if these northeastern spiders grew to adults and survived the winter? Did they find another full grown Joro spider to mate with? Or did a happy cardinal snatch it right out if its web for a quick snack? We can’t yet say that they have been established in Massachusetts or Pennsylvania. Time and more data will tell.

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/243429720

Freak out level

Should we be freaking out? Not in any sci-fi type way. These spiders are nothing like the flying monkeys in the Wizard of Oz. Your pets and children, and YOU are safe. It’s our native orb weavers who may have some issues with the new neighbors. Joro spiders build large webs, are out in the day AND night, and don’t mind living closely to each other. Oh, and they’ll eat other spiders too. Once they move into the neighborhood, it makes sense that the locals would move out or die out.

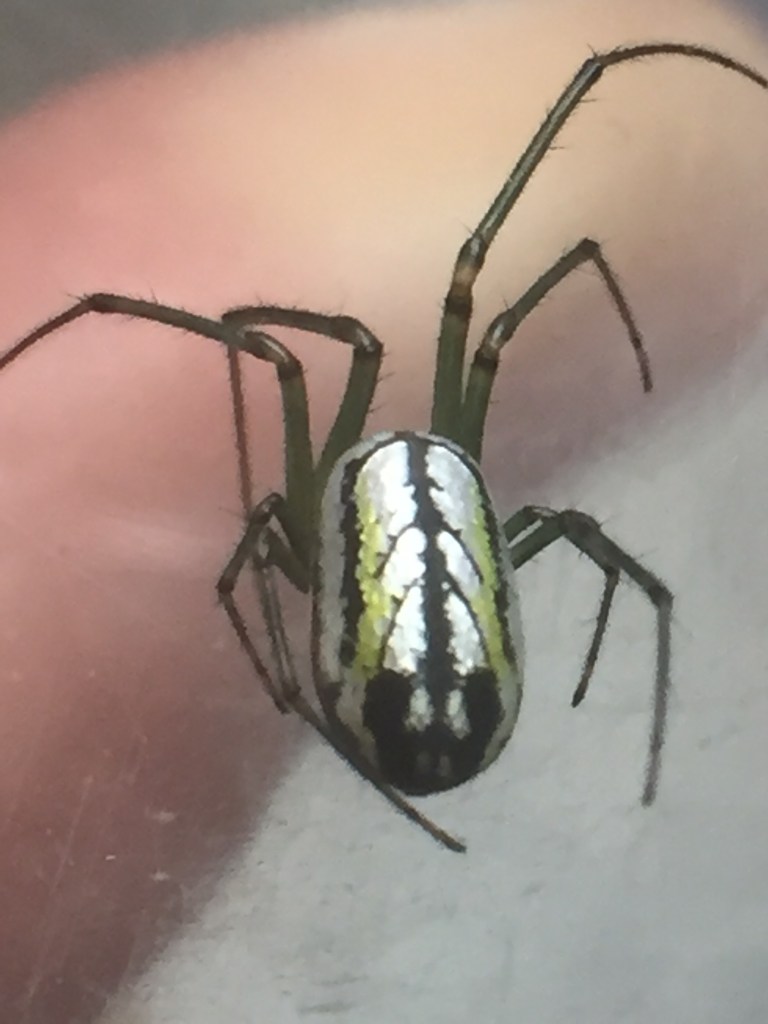

Should we be stomping on these spiders akin to the spotted lantern flies? No. If you can’t tell which spider is the Joro spider in the photos below, then you could be killing one of the natives (answer at end of article). It’s bad luck to stomp on spiders anyways, so be mindful! Instead of being afraid, we should be observant. Scientists are eager for data – even where Joro spiders AREN’T being found.

I hope the sensational articles will slow down as many spider researchers and enthusiasts have countered them with a more level-headed explanations. The Joro spider offers an opportunity for new research. We have a ton of research on invasive plants and insects, but not invasive spiders. The general public can make an impact on this research if they are being informed in a more acceptable manner rather than being scared to death. If you think you’ve spotted a Joro spider, report it, observe it, pay attention. What’s it eating? What’s trying to eat it? You might find a new Zen in spider watching and realize that scary, creepy, venomous spiders are more fascinating than you could have ever imagined.

Oh, the answer to which one of the photos was a Joro spider is…none of ’em. A. is Argiope aurantia (aka banana spider, black and yellow garden spider, zipper spider, Steeler spider, and a whole bunch of other regional nicknames). B. is Leucauge venusta (aka the orchard orbweaver), and C. is Trichonephelia clavipes (aka golden silk orbweaver, calico spider, banana spider). All three are native or naturalized and are a vital part of the natural food web!

Sources:

Chuang, A. et al. (2023), The Jorō spider (Trichonephila clavata) in the southeastern U.S.: An opportunity for research and a call for reasonable journalism. Biol. Invasions, 25, 17–26.

Davis, A.K., & Frick, B.L. (2022) Physiological evaluation of newly invasive jorō spiders (Trichonephila clavata) in the southeastern USA compared to their naturalized cousin, Trichonephila Clavipes. Physiol. Entomol., 170–175.

Giulian, Joseph et al. (2024) Assessing the potential invasive range of Trichonephila clavata using species distribution models. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. Volume 17, Issue 3, Pages 490-496.

Hoebeke et al. (2015), Nephila clavata L Koch, the Joro Spider of East Asia, newly recorded from North America (Araneae: Nephilidae). PeerJ 3:e763; DOI 10.7717/peerj. 763.

Nelsen, D.R. et al. (2023) Future spread and ecological impacts of a rapidly expanding invasive predator population. Ecol. Evol. 13, e10728.

Pemberton, R. W. (2025). Explosive Growth of the Jorō Spider (Trichonephila clavata (L. Koch): Araneae: Araneidae) and Concurrent Decline of Native Orbweaving Spiders in Atlanta, Georgia Forests at the Forefront of the Jorō Spider’s Invasive Spread. Insects, 16(5), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16050443

Rose, S. (2022). Spiders of North America. Princeton University Press.

great article! You’ve taught me a lot about these spiders! Keep doing whatcha do!❤️

LikeLike