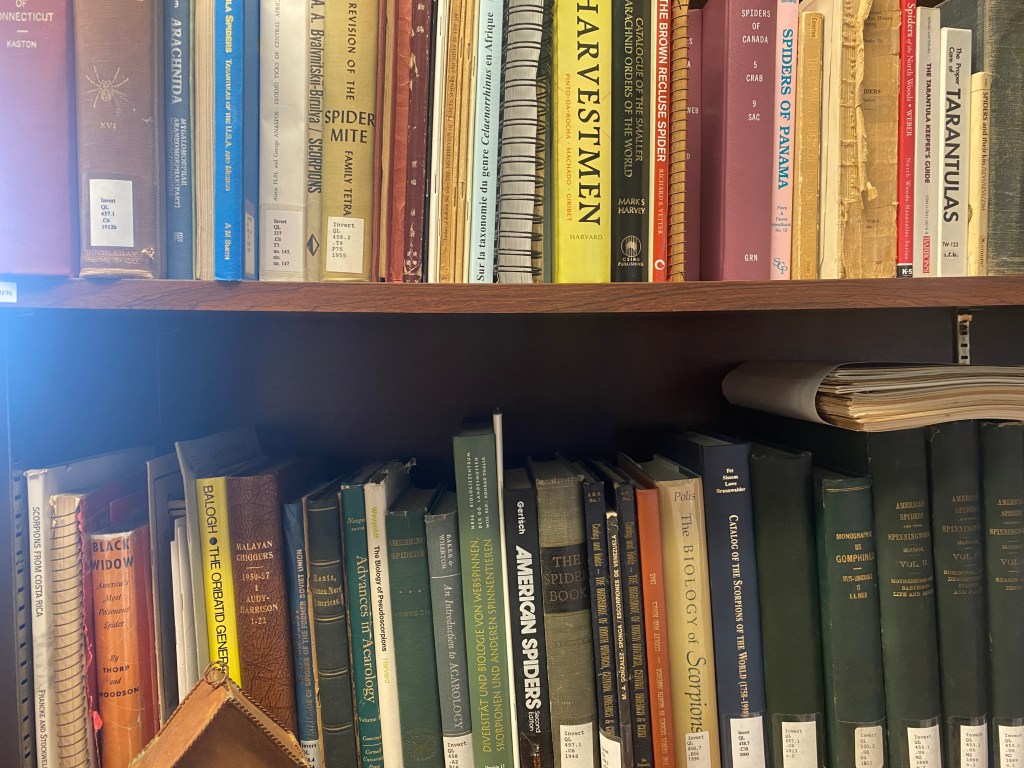

I volunteer at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History once a week. I get to go behind the doors that say, “Research Staff Only”, into the backroom of the Department of Invertebrate Zoology (IZ), the place where researchers spend their days identifying and curating bugs. I love it there! It’s like being in the library of an old mansion where dark, wooden shelves house ornate, leather-bound books with Latin titles. There are secret passageways and corridors stacked with drawers and jars of ethanol-soaked insects, arachnids, and crustaceans. The people that work there are basically bug nerds who speak the language of binomial nomenclature and, who, like me, think jointed appendages are beautiful. They preserve, organize, and care for millions of invertebrates and are extremely generous with their knowledge. Scientists from all over the world will come to visit or borrow the delicately pinned moths, butterflies, and beetles. The small display you see in the 3rd floor hall is just a fraction of what’s behind those office doors.

I thoroughly enjoy my time there; it’s quiet, cozy, and I get into a sort of Zen while I’m working. I’m honored to have to opportunity to help out with the spider collection. It was a wavy road to get there. My confidence often pendulums from extreme self-doubt to bold determination. “I’m just a spider enthusiast” to “I actually know A LOT about spiders!” When I first approached the IZ department to volunteer back in early 201?, I specifically stated interest working with the spiders. I was told that my enthusiasm was appreciated, but since I wasn’t a specialist in any of the spider families, it wouldn’t be helpful. I left feeling rejected, but that didn’t stop me from seeking out other “spider people”. One such person was Charles Bier from the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. He was a research associate and volunteer at the museum in 2008/2009. He shared everything he knew about his brief experience with the spider collection. He also shared his personal presentations and spreadsheets of resources. Most importantly, he was super supportive and has remained a valuable ally to me ever since.

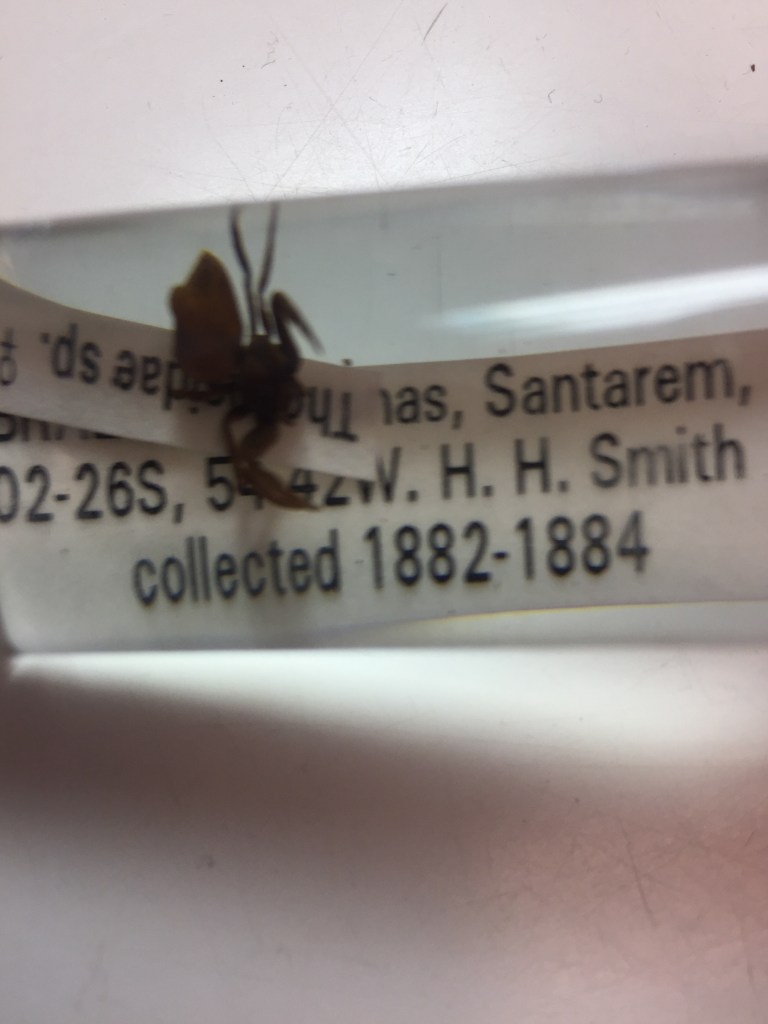

Another chance at the museum opened up for me many years later in 2019 when J. Murphy emailed me with a spider question and said she was volunteering at the museum working with the spiders. WHAT?? Curatorial Assistant, Cat Giles, had taken an interest in the the spider collection which hadn’t been given any love since Charles was there. Now that there was a spider “manager” the doors opened to support volunteers and I jumped in immediately. My first assignment was data entry of the spiders as they were being identified by Cat and J. I got to type in all the cool info about where the spiders were found, who collected them, and when they were collected. Some specimens dated back to the late 1800s! Most spiders were eastern US, a lot from Allegheny County, many deposited from personal collections, and a lot from expeditions to Brazil and the Dominican Republic.

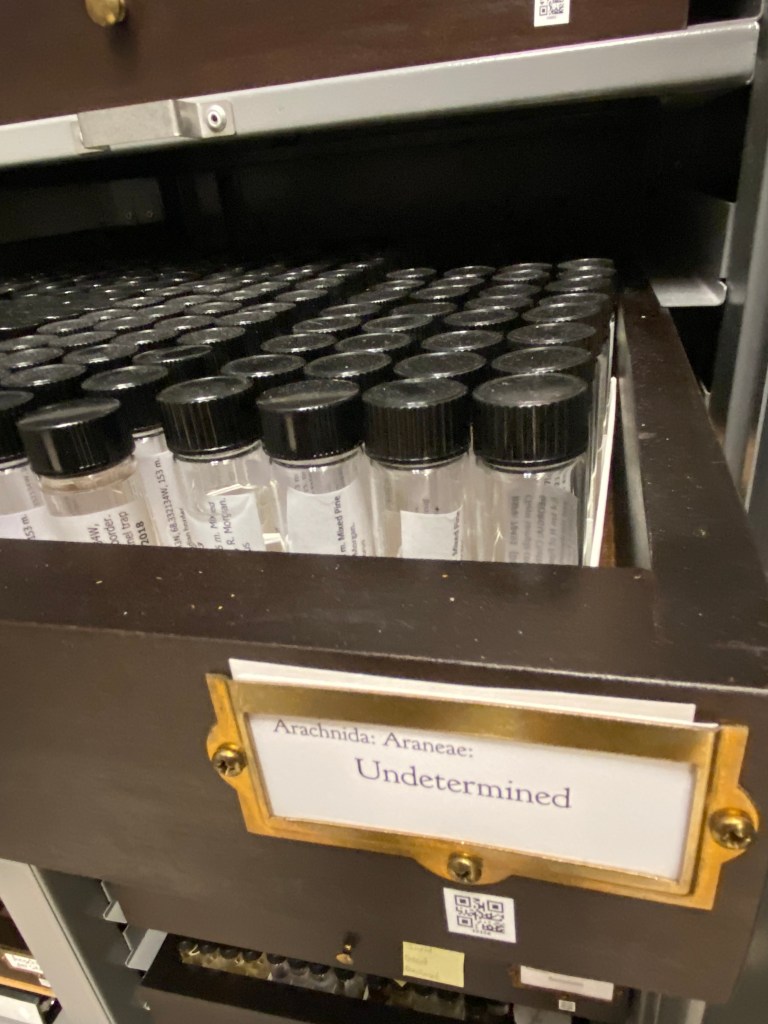

Then stupid Covid hit. Cat got furloughed and moved onto other things. Another volunteer, Val, and I started getting back into the spiders when everything reopened. Even though there wasn’t an official “spider manager” we knew what we were doing and picked up where Cat left off. Val is a database wizard and helped launch a more formal arachnid database for the museum via Ecdysis. After having entered all of the already identified spiders, we were able to dive in and start identifying the remaining thousands of spider vials that hadn’t been sorted. Val specializes in jumping spiders and I’m a generalist, wanting to know a little about everything! Identifying spiders is one of my favorite things to do! It’s like solving a puzzle and there is a whole giant cabinet full of puzzles to solve!

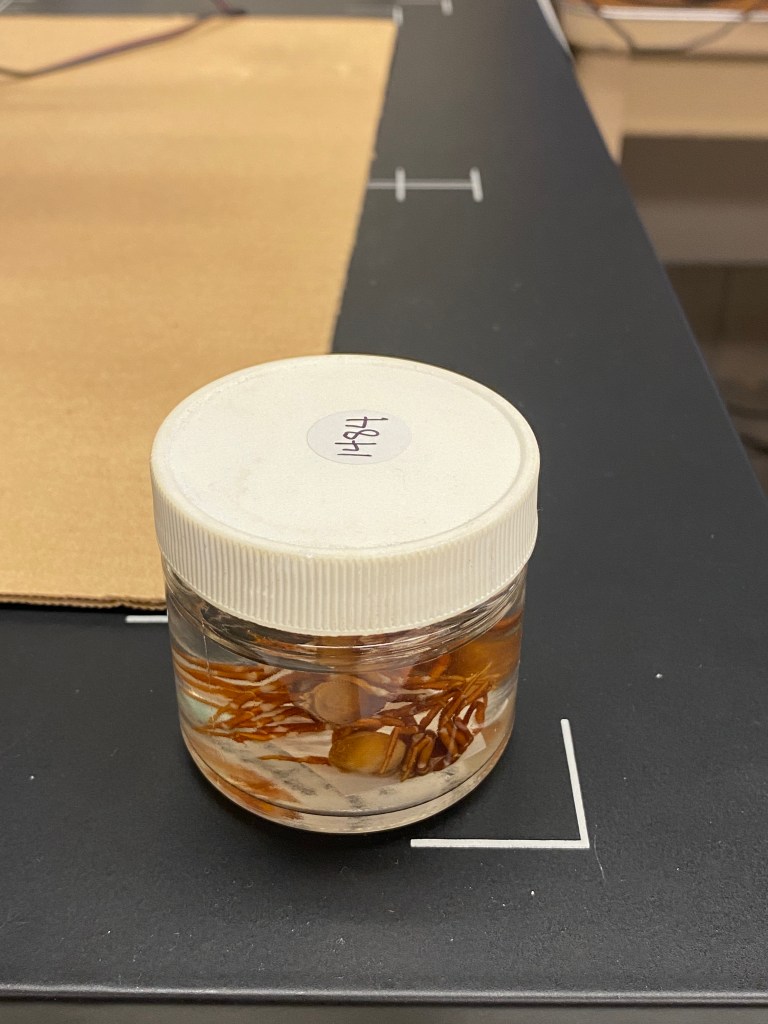

One such puzzle jumped out in spring of 2025. A two-ounce jar of four, large spiders was up next in the drawer I was sorting though. The spiders were collected in West Virginia back in 1994. A closer look under the scope revealed they were a type of trapdoor spider. I could tell because of the thick, robust legs, the eyes were small and clustered on a mound, and the fangs pointed down (paraxial) instead of towards one another (diaxial).

I was excited because I had never seen this type of spider outside of a field guide. These trapdoor spiders have cork-looking, extremely ribbed abdomens. It was easy to key them out to genus in the Spiders of North America ID manual: paraxial fangs > abdomen without tergites (hardened plates) > 3 claws, no claw tufts > spinnerets short > abdomen truncate, hardened, and with grooves > Cyclocosmia genus. Two species are known north of Mexico; found in southeastern states. Hmm. These guys were collected in West Virginia – hundreds of miles out of the typical range for this genus. I made a mental note and moved onto the next vial.

Curious about the same thing, Val followed up by finding the taxonomic revision of Cyclocosmia (Gertch and Platnick, 1975) and tried to key the spiders to species. This process involves counting each of those grooves or ribs on the abdomen which turned out to be a tedious process, not straightforward at all. The West Virginia specimens weren’t jiving with the key, the rib count on all four of them wasn’t matching our two native species. Could this be a new species? Nahhh.

I went online and dug up a more current paper describing Cyclocosmia and emailed all contributing authors about the find asking if they might be interested in checking it out. One of the authors responded and said we should contact Dr. Sherwood who had recently described a new species of Cyclocosmia in Vietnam, so I did. Dr. Danniella Sherwood replied from the UK and we began a nine month email correspondence. She shared very specific requirements for photos of the spider’s palps, which would offer a more definite diagnostic rather than just counting the number of abdominal ribs.

I removed the palps and used my go-to photo technique where I hold my phone up to one of the microscope eye pieces and zoom in. This method works great for me, but was not focused enough for the minute details that needed to be seen. This led to another really cool experience, learning how to take stacked images which results in excellent resolution – the entire object being photographed comes out crystal clear. Val had some experience with this and with help from Curatorial Assistant, Vanessa Verdecia, we were able to access the IZ camera that was set up for this exact thing and took some gorgeously detailed photos complete with scale bars.

Dr. Sherwood provided her specialized eye from across the pond and determined, YES, this looks like a new species! She just had to double check on a few other things to “exhaust every possible avenue to show [the palps] are different.”

A few months later, Dr. Sherwood reached out again. Amidst her work gathering papers, doing grant applications, student appraisals, presentations, AND preparing for an expedition to the Carribean, she had been steadily tracking down clues to prove, without a doubt, that we had an undescribed species.

“I’d like to see the bulb if possible because that is best practice (that I set for the field) instead of just relying [that] it ‘looks the same’ as C. truncata palpal bulb. The second most important thing is the lateral photo of the abdomen, if we find the ribs don’t protrude like C. torreya that is enough on its own for me to move my 99% confidence to 100,” she wrote in a December 2024 email. She asked us for some more anatomical photos with clear instructions on which parts, which views, and included photo examples of what she needed to add to the draft paper. She also had an idea for the name of the new species!

Reading the draft, I was really excited to see our photos included in paper. We made some edits and anxiously waited for that final 1% of doubt to be resolved. Turns out, if you hadn’t already predicted based on the title of this blog, a new species of trapdoor spider, Cyclocosmia johndenveri, was confirmed and named after the singer/songwriter, John Denver, who recorded the song, “Country Roads, Take Me Home”. Cyclocosmia johndenveri was introduced to the public on March 2025 via the journal Natura Somogyieni.

For me, this was an epic event! At the risk of sounding naive, when I first looked at the draft Dr. Sherwood sent us, I was anticipating finding my name among the thank yous or acknowledgements. When I didn’t see it, I felt that pang of rejection as the pendulum swung towards the “not an expert” side. I had totally overlooked the fact that Dr. Sherwood had included Val and I as co-authors. When I saw that a moment later, I jumped from my chair in surprise! I had co-authored a taxonomic, published paper! How did this even happen?

Aside from documenting the experience, a big part of me wanted to share this story to encourage and inspire anyone else who ever thinks they’re “just an enthusiast”. Find your allies. Don’t be discouraged (for too long). Keep being nebby (in other people’s business) and there is no shame in advocating for yourself. I sincerely appreciate the team effort involved in finding this spider among the thousands of vials and all of the support we received from the museum and especially Dr. Sherwood, who patiently directed us throughout the process.

It’s a testament to how a variety of experience and backgrounds can unite and provide impactful contributions to science. The experts and specialists have worked really hard to get where they are and often have multiple things happening at once. To them, I have much respect and admiration. I got weeded right out of a biology degree because I suck at numbers. I’m more of a kinaesthetic learner. Right brained, if you will. This journey has helped me embrace all of my experience AND inexperience. Anyone can contribute. It’s one of the many examples of how blending specialists with citizen scientists can result in a really cool discovery!

Gertsch, W. J. & Platnick, N. I. (1975). A revision of the trapdoor spider genus Cyclocosmia (Araneae, Ctenizidae). American Museum Novitates 2580: 1-20.

Sherwood, D., Warhol, V. & Bianco, A. 2025: Country roads, take me home: Cyclocosmia johndenveri, a new species of trapdoor spider from the mountains of West Virginia (Araneae: Halonoproctidae). – Natura Somogyienis 45: 27-40.

Congratulations Amy! I’m jealous, I’ve found a few specimens that may be new species here in our Ohio collection, but they belong to groups of Linyphiids that are crammed with undescribed or poorly described species. The project is going to take someone a lot of time and resources to solve these mysteries by revising the entire group. So this is beyond my grasp at the moment. I’m so happy for you, and such a fun beautiful species!

LikeLike

Thank you so much 🙂 Yes, the Linyphiids intimidate me, lol! You probably do have a new species or two! That revision will be mammoth, whew!

LikeLike

Congrats Amy. You are a true Spiderologist. You must really love it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Gene!

LikeLike