Below are a dozen spider sacs pictured with their adult counterparts. The range is eastern US, mostly Western PA, but I frequently visit relatives in Florida and the Carolinas so there are some representatives from there. Most of the sacs pictured were made or hatched in captivity so I could get an identification. Sometimes, what came out of the sac was definitely a surprise (see Egg Invader). In the wild, spider eggs can be very well hidden because many bugs and animals have them on the menu; they are definitely not at the top of the food chain. Some of the designs of these sacs are so clever, I didn’t believe they belonged to spiders until I witnessed the creatures actually constructing them. The different sac designs can be very unique and might help you ID what kind of spiders you have around even if the actual spiders aren’t there anymore Check out The Egg Sac Gallery for more examples.

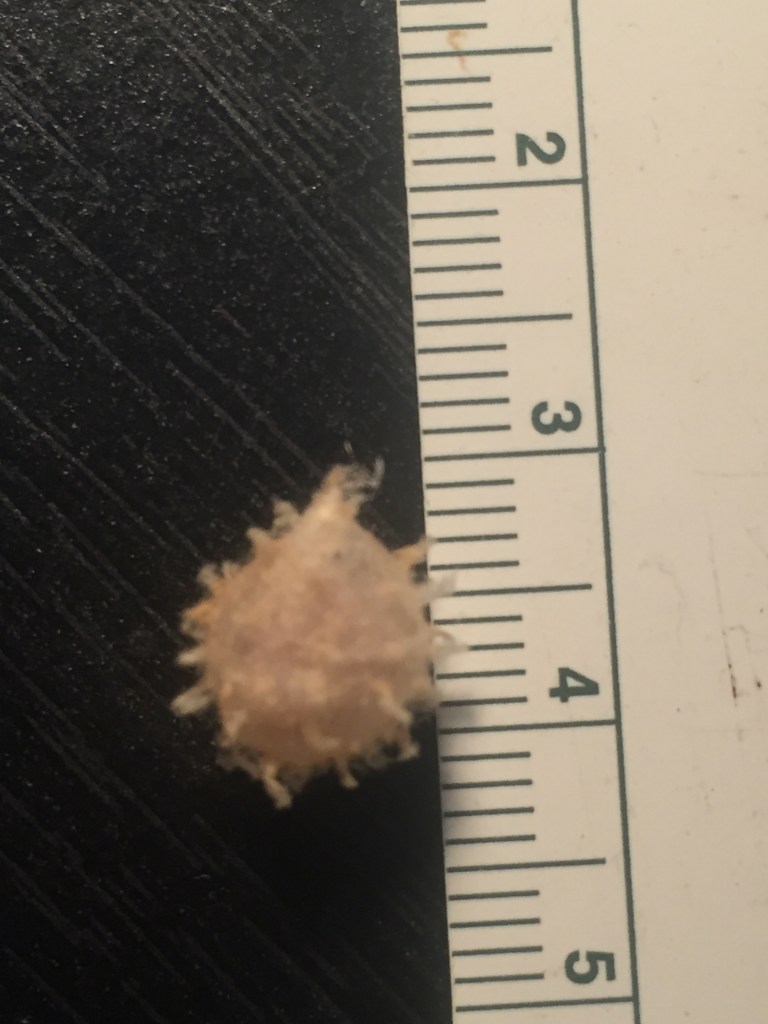

Hammock Spiders

This small cottony poof is made by the Pityohyphantes genus, commonly called hammock spiders. Their web looks more like a dome rather than a hammock. These spiders are smallish, around five to six millimeters from head to butt. They have exceptionally beautiful markings and are commonly found across North America. I’ve found the spiders among spicebush shrubs in the woods, hiding under tree bark, and on the wall in a composting toilet restroom in Ohio. The moms fasten their egg sacs among the leaves and twigs and the spiderlings are on their own from there.

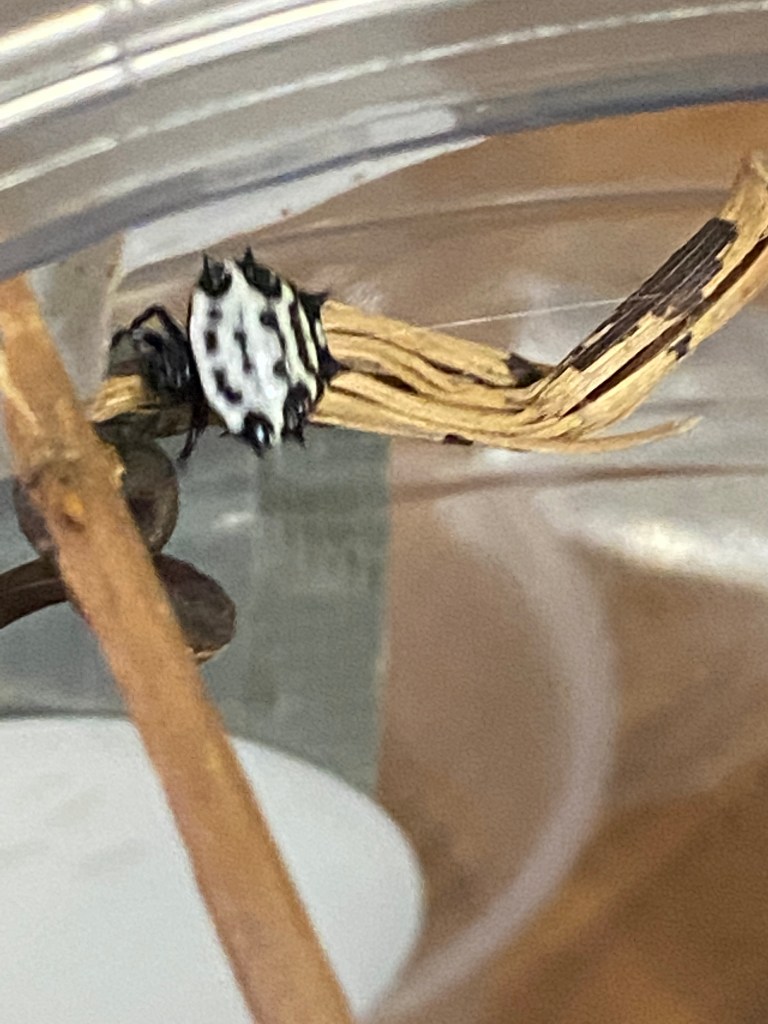

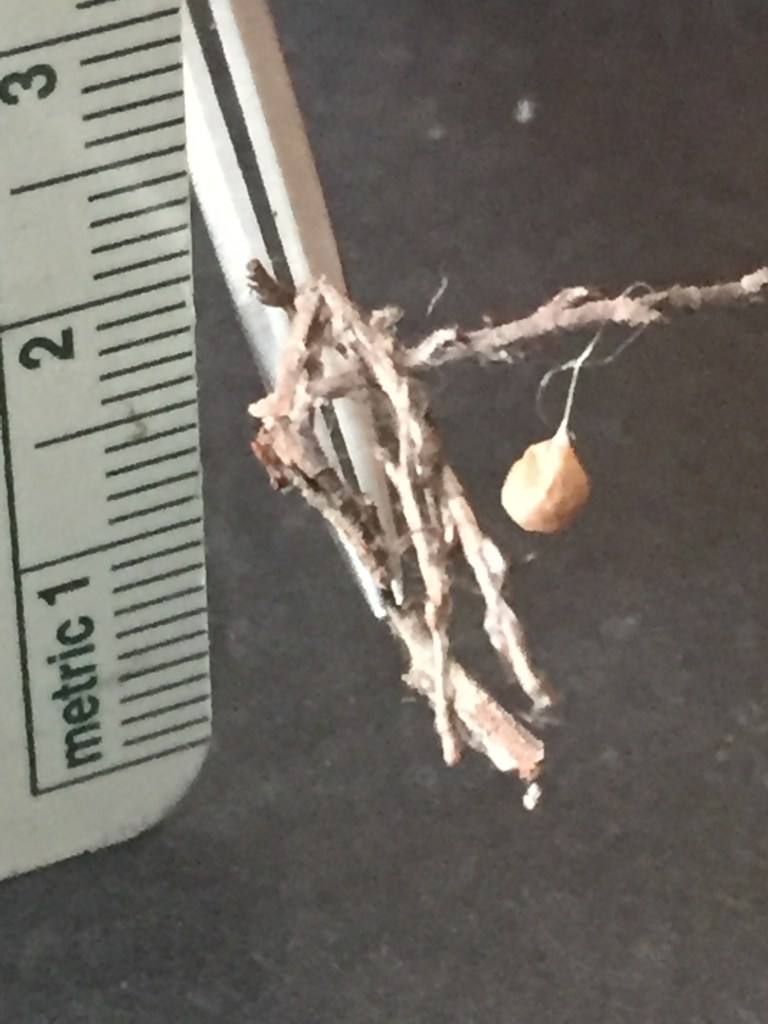

Brown Widow

The Brown Widow (Latrodectus geometricus) is not found in Western PA, but is becoming more common in the southeast as an introduced species. There is concern that they are displacing the native black widows. They are definitely numerous and more easy to find. Brown widows have a very distinct egg sac that resembles a flail. Other widow species egg sacs do not have these projections. I found out about “dark brown” widows this way. I thought I had caught a Southern black widow (Lactrodectus mactans) after only finding brown widow after brown widow. I was bummed to find I just had a dark version of another brown widow because it made a spiky egg sac. The egg sac was the diagnostic.

Like most spiders in the Theridiidae family, which Latrodectus falls under, the sacs are suspended in the web near the mom and there is often more than one sac. The mom offers some protection but the spiderlings can survive without her.

Are they venomous? Yes. All spiders except one family (Uloboridae) have venom. Spiders in the Latrodectus genus have venom that is medically significant to people meaning a bite could cause considerable pain. Death is extremely rare. Brown widows have less potent venom than other widows, plus, they’re shy and will retreat at the slightest disturbance. The ones pictured here were caught in Jacksonville, NC in a bike trail tunnel. I’ve also found them (in North and South Carolina) under house siding, patio furniture, and around sheds. They like to hide, but their tell-tale, spiky egg sacs give them away.

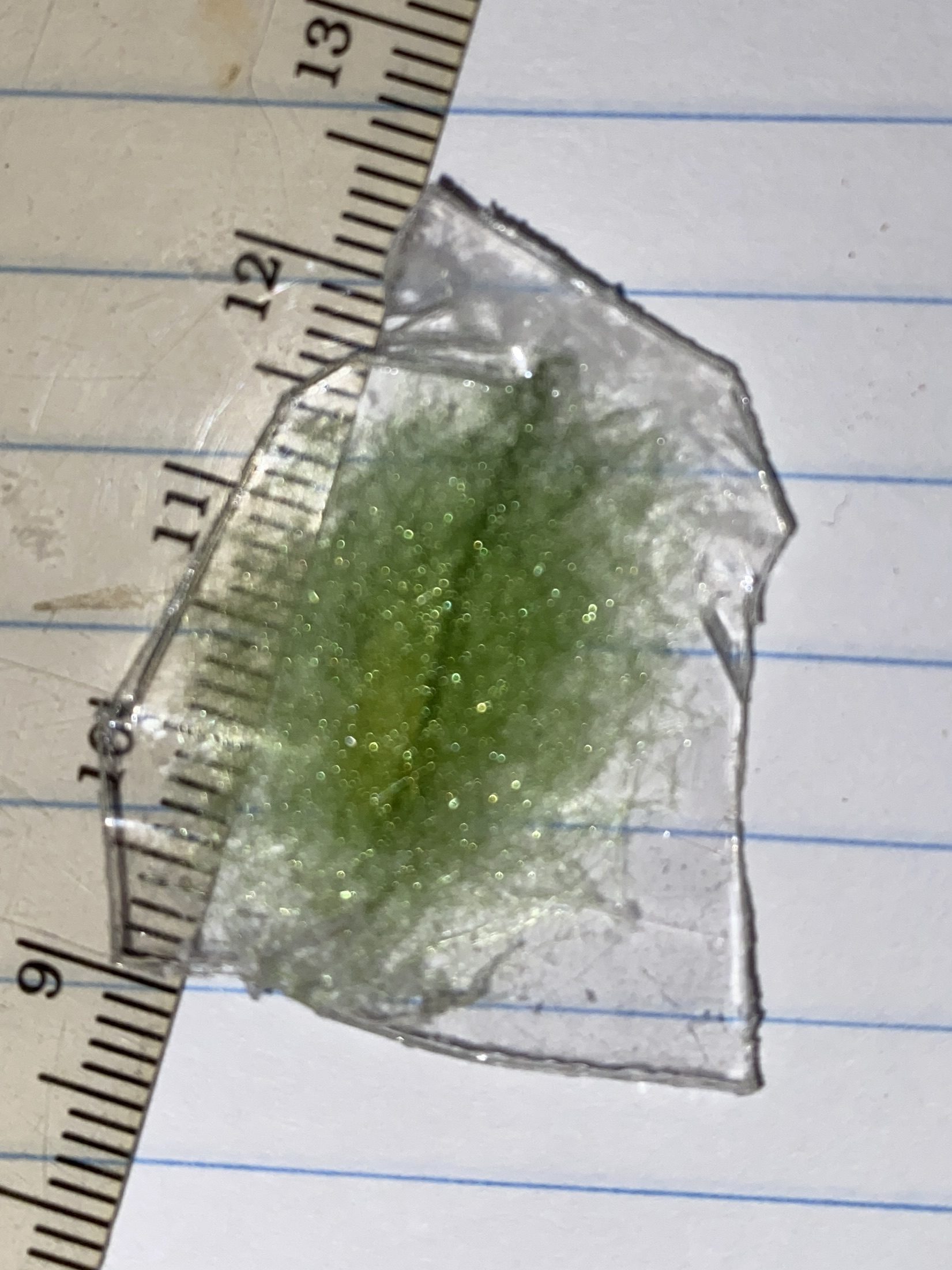

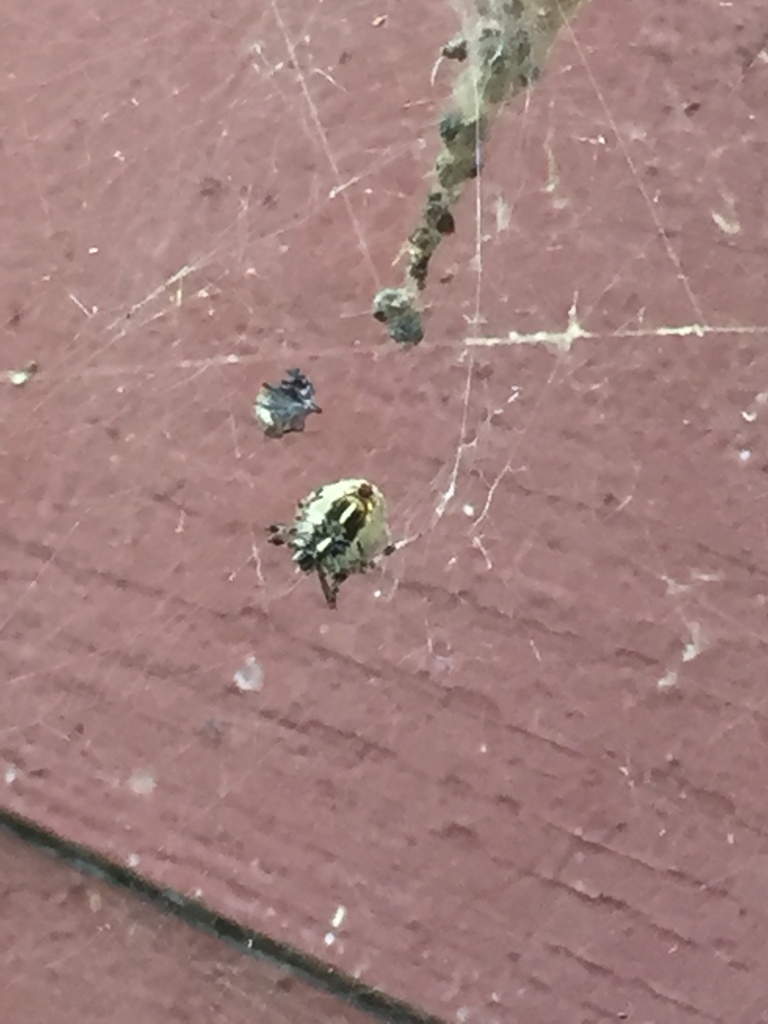

Spiny-backed Orb Weaver

Since we’re checking out spiders from the southeast, here is the green, “zippered” egg sac of Gasteracantha cancriformis, commonly called the Spiny-backed orb weaver. The spiny-backed orb weaver is about the size of a penny, but makes dinner-plate-sized webs in big openings, like between trees. The frame attachment lines which hold the orb web can easily span several feet and are usually found in low-traffic areas. I was keeping a wild caught female in captivity and I didn’t know it, but she had mated, and the green, silken sac appeared. I imagine the silk is green to blend in with leaves. Since there were no leaves, she used the side of the plastic container and it stood out right away. I could not remove the sac without damaging it so I cut the plastic around it. That’s what you see in first photo. Once the mom deposits her eggs, they’re on their own! Despite the pointy, jagger-lookin abdomen (jagger means thorns in Pittburghese), these spiders are completely harmless!

Pirate Spiders

One of the most fascinating spiders ever, the Pirate spider! They don’t make their own webs. They invade existing webs and eat the resident spiders using luring tactics and very potent venom (potent with spiders, not humans). The egg sacs have a reddish, woolly appearance. They seem to be left suspended in random places and are left on their own. I’ve found the actual spider in park restrooms, friend’s dining rooms, and outside along concrete walls. They are around five millimeters long and the first two pairs of their front legs are really, really spiny. Watching these guys doing their pirate thing is amazing although I feel badly that they’re eating other spiders. More info on these guys can be found in the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Cellar Spiders

The cellar spiders (Pholcidae family) change things up a bit. These spiders are widespread and common among rafters in basements or in undusted corners. The webs are like an invisible labyrinth, you can hardly see the silk. The spider rests hanging upside down. They loosely connect their eggs with a few lines of silk and then cart the eggs around holding the tiny package with their chelicerae (fangs). Moms will stay in their webs with their sacs. When they hatch, the web becomes communal for a few days until the little ones disperse. If you didn’t notice mom with a ball in her mouth, you probably didn’t even know she was adding more spiders to your cellar. Which is not a bad thing. Free pest control. These guys are totally harmless and actually fun to have around!

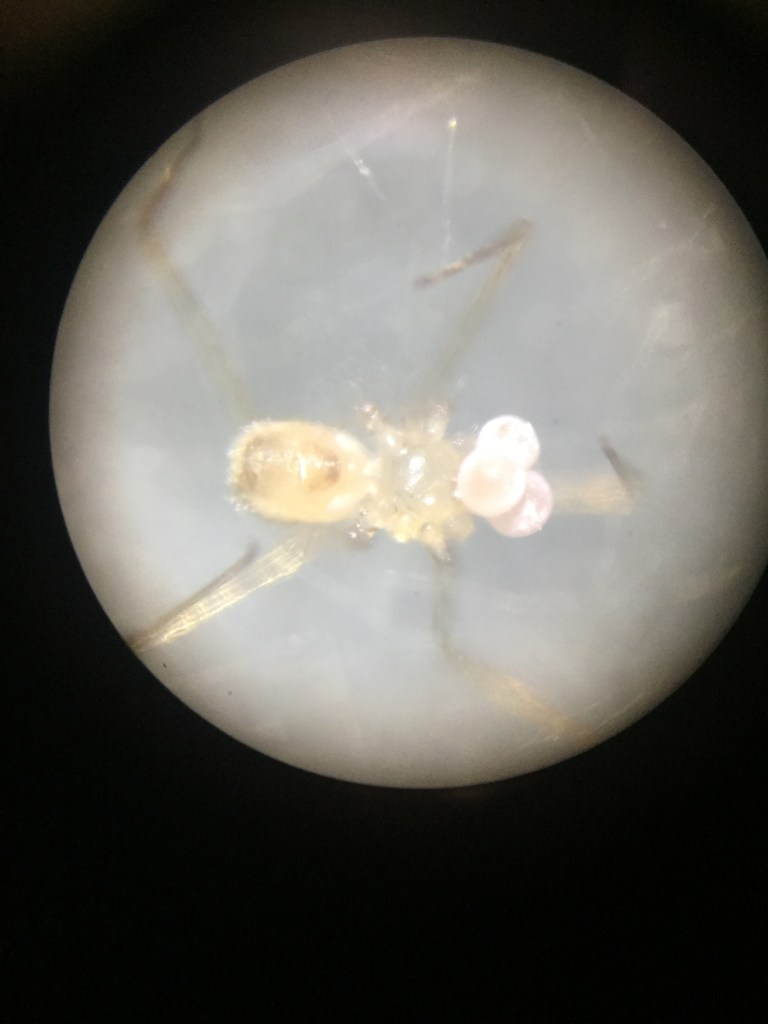

Phrurotimpus‘ pink discs

This shiny gem of a spider makes flat, papery discs that don’t even feel like silk. This is an egg sac from Phrurotimpus in the Phrurolithidae family. These are small, spiders often found under things like stones or bark. They will guard their egg sacs although parasites have come up with very sneaky ways to eat them anyway. These spiders are quite small and shy so you’re more likely to see the sac instead of the spider. I often find these attached to stones where there’s a divot or dent in the rock and I always wondered what those red things were until I caught one that was gravid and she attached her egg sac to the side of the plastic enclosure.

Fishing and Nursery Web Spiders (Pisauridae family)

Spiders in the Pisauridae family are often mistaken for wolf spiders due to their large, leggy sudden appearances in wood piles and along stream banks. They have a characteristic splayed resting posture that makes them look enormous. Like wolf spiders, Pisaurids tote their precious package around with them. Unlike wolf spiders they carry the sac with their chelicerae (fangs) whereas wolf spiders carry theirs behind them like a tow truck. The egg sac is bluish in the left pic below, but that was quite odd. I still don’t know why it was blue. They are typically off-white and adorned with random dirt and debris and can be as large as an inch in diameter. When the eggs are ready to hatch, pisaurids will fasten the sac to vegetation and weave a nursery web around it. The spiderlings hatch into the web with mom on the premises. They don’t climb on her like they do with the wolf spiders, but the babies hang out communally until dispersal. Since these spiders are hunt/ambush spiders, they don’t make a capture web so if you see one hanging around a plant that has a good bit of silk nearby, that’s probably the nursery!

Brown Recluse

Recluse spiders make white, frizzy retreats where they hang out. They will make their sacs in these retreats and sit right next to them. The sacs look like raised pillows amongst the fuzz. “Chance”, my mama brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa), had three in her retreat. The spiderlings and mom hung out together for about a week and then I separated them. Although mom guards the egg sacs, she wasn’t aggressive, but would freeze when I’d go poking in there with big movements. The silk of the recluse spiders is very wooly and will reflect brightly when illuminated with a black light. “Chance”, the spider pictured was born and raised in captivity. Read more in Yinzer Recluses.

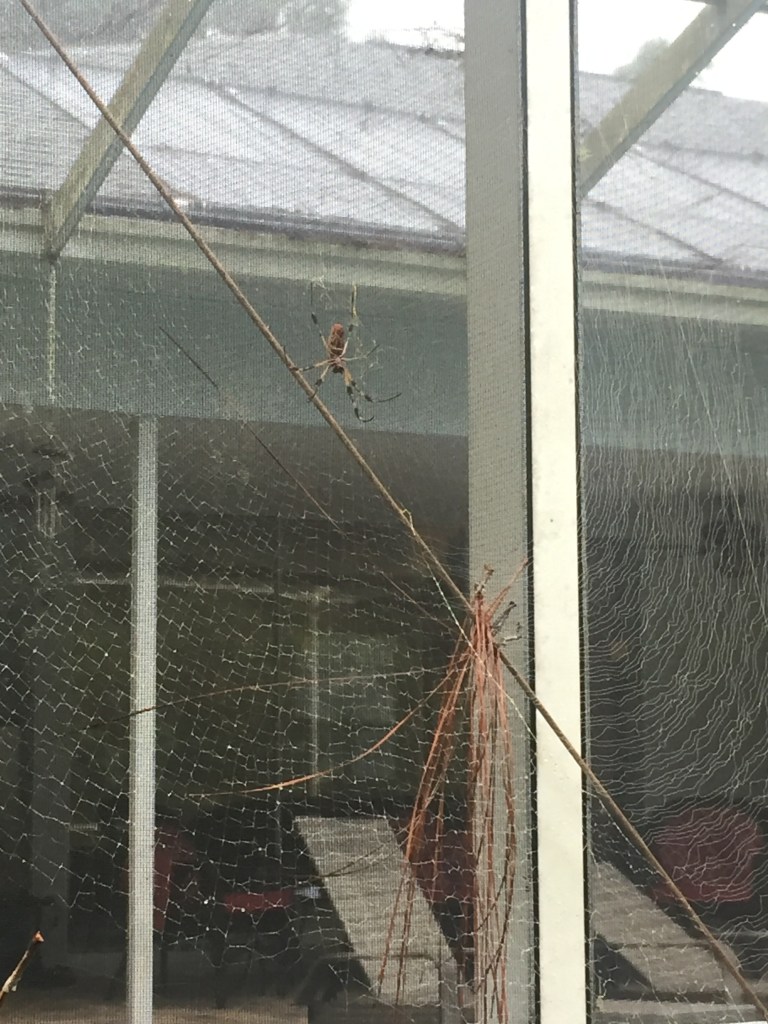

Dewdrop spider

This tiny little spider sneaks its food from other spiders. I found this one in a golden silk orb weaver web. The size difference between the two spiders is so great that the dew drop spider lives in the web undetected and eats all the little stuff the big spider ignores. Its egg sac hangs off of a tiny stalk and is only a few millimeters wide.

Trashline and Labyrinth spiders

A few spiders incorporate their sacs in their webs. The trashline orb weaver (Cyclosa genus) has them mixed in with bug remains and other debris in a vertical line. The mom sits in that line, too, and you often can’t tell which lump is the actual spider. The labyrinth spider and basilica spider also bunch their sacs in a row, but more conspicuously.

Argiope egg fail

I found an Argiope aurantia crawling across a concrete plaza on a cold night in November. This is really odd behavior for this type of spider which would normally be found in a web. They don’t walk well on the ground as their legs are better suited for silk stepping. She was struggling and fumbling. In November, these girls are at the end of their lives. She looked fat and was probably full of eggs. I took her home and set her up in a container and sure enough, overnight, she attempted to deposit her eggs, but her attempt failed. She was dead the next morning. I felt so sorry for her. She did her best with what little strength she had left. She made the top and bottom of her sac but they were in two different places. Her eggs were laid in the top half with no bottom. They basically dripped down hanging like a yellow stalactite. I knew it was probably never going to work, but I gently gathered the exposed eggs and piled them onto one of the sac halves. I used a small ball of cotton as a lid and wound some of her silk lines around to hold it in place. I suspended the sac from a twig and waited. Nothing happened. Meh, it was worth a shot, long as it was. I included this story to highlight the complicated process we usually don’t get to witness and also the innate drive spiders have to reproduce, even on their last legs!

Sources:

Almeida, R., Ferreira Junior, R., Chaves, C., & Barraviera, B.. (2009). Envenomation caused by Latrodectus geometricus in São Paulo state, Brazil: a case report. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases, 15(3), 562–571. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-91992009000300016

Bristowe, W. S. (1958). The World of Spiders. Collins London.

Rose, S. (2022). Spiders of North America (Vol. 154). Princeton University Press.

Ubick, D., Paquin, P., Cushing, P.E. and Roth, V. (eds). 2017. Spiders of North America: an identification manual, 2nd Edition. American Arachnological Society, Keene, New Hampshire, USA.