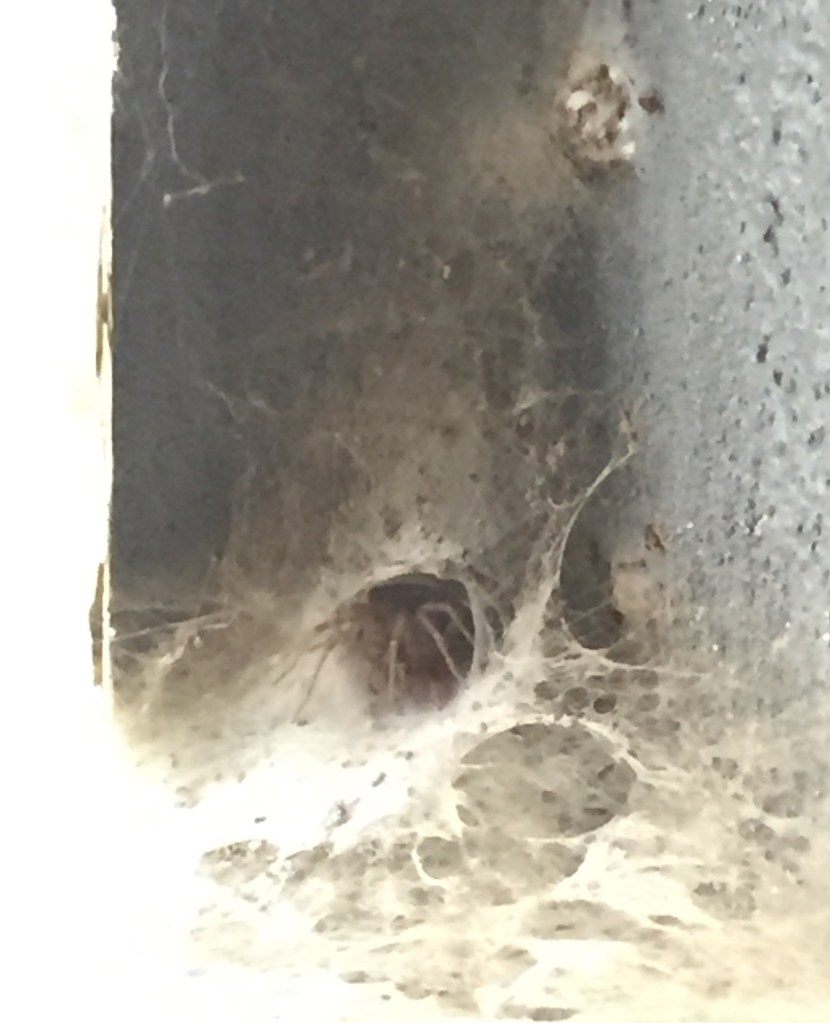

If you have a basement, like most of us in Western PA do, you probably have your very own population of these cool, harmless spiders. Commonly called barn funnel weavers, Tegenaria domestica are large (ten millimeters from head to abdomen), brown spiders that make flat webs with a tunnel in a corner or crevice. They seem to love glass block basement windows.

Tegenaria domestica (barn funnel weavers) are nocturnal and can be seen sitting just inside the tunnel, legs fanned out, waiting for a vibration. If startled by a big vibration, they quickly retreat into the tunnel, which really just goes down along the corner a few centimeters. If there is a smaller vibration, like a fly, the spider is ferociously quick and will dart out, bite, and drag the fly back into the tunnel. The crisscrossing silk strands that make the sheet-like web are not sticky so arthropods can easily clamber off of the web, but the spider is so fast, whatever has landed on the web has very little chance to escape!

Barn funnel weavers (Tegenaria domestica) are just one kind of spider in the Agelenidae family which includes grass spiders and hobo spiders; all make the characteristic funnel-shaped web. We don’t have hobo spiders around here. I’ve collected spiders from friends’ houses who thought they had hobo spiders and they’re always barn funnel weavers. Barn funnel weavers are originally from Europe and arrived in America with the first travelers by sea. They’re basically American citizens now, having naturalized comfortably among humans. They’ve even taken their allegiance a step further by offering invasive pest control. Barn funnel weavers are one of the few spiders that will eat the spotted lantern fly, which is plaguing Western Pennsylvania right now.

Tegenaria domestica will eat a variety of other arthropods such as potato bugs, millipedes, flies, crickets, other spiders, and centipedes, basically anything they can overpower. I tossed an earwig into one of my resident spiders webs to see what happened. The spider attacked immediately, but the earwig fought back enough that the spider retreated and the earwig was able to run off.

These spiders usually stay right where you can see them, except in June, when the males are on the move looking for females. They can also be accidentally uncovered (and they take off running) if you’re rummaging around boxes or other stuff that’s been sitting around for a long time. Some end up in unfortunate places like the sink or washing machine and are unable to get themselves out because they can’t climb smooth surfaces.

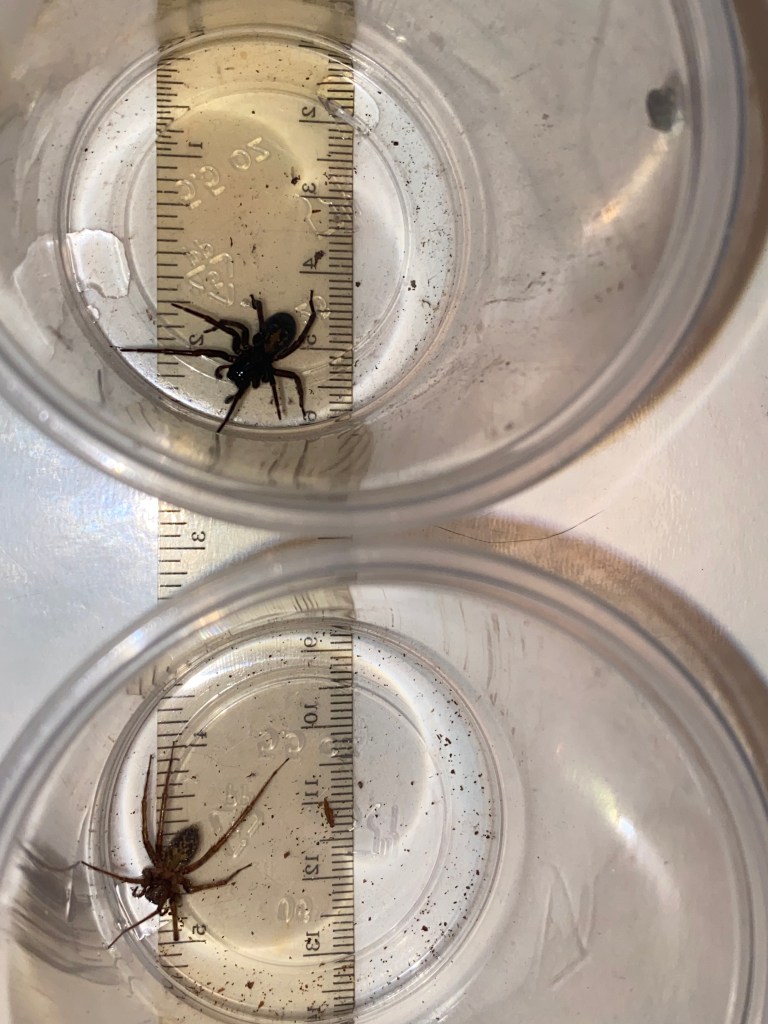

Barn funnel weavers can easily be confused with other spiders when they’re out of their webs. To most people, they see a big, brown spider that materialized out of nowhere tiptoeing at top speed towards the nearest darkness. Up close, barn funnel weavers have lots of spines and hairs which gives them a slightly fuzzy appearance. The legs are lightly banded and are about equal size. There are two dark stripes on the head that go front to back and the abdomen has chevron markings. Compared to wolf spiders (Lycosidae family), they have thinner legs and lack the large posterior median eyes that wolf spiders possess.

Another look alike is a dark, thick spider called a hacklemesh weaver (Amaurobiidae family). The hacklemesh weaver is another harmless, beefy, brown spider that likes the dark. Hacklemesh weavers don’t have the two stripes on their heads. Their heads are bald, shiny, and kind of squarish. And their legs are shorter and thicker. Lastly, Hacklemesh weavers don’t make flat funnel webs like the barn funnel weavers do which is a giant clue, but when both are free roaming, a closer look is necessary.

I recently observed some odd behavior with all of the Tegenaria domestica action I’ve had in my basement this summer. On my way down to do a load of laundry, I noticed a T. domestica in its web and another one just about seven inches away. When I got up close, I noticed it was the male in the web and the female was sitting out, exposed. That’s odd. It’s usually the males who wander while the females stay in their webs. I thought maybe it was a fluke. Perhaps the female deserted her web and just happened to be near this guy’s web en route to new corners. Maybe the male spider hadn’t left its web to search for females, yet. I never really paid attention. I thought it was interesting, but carried on with housekeeping. However, a short while later, in another part of the basement, I saw the same thing with two different spiders. A male was in the web with a female resting close by. Now I started thinking is this typical behavior for this type of spider?

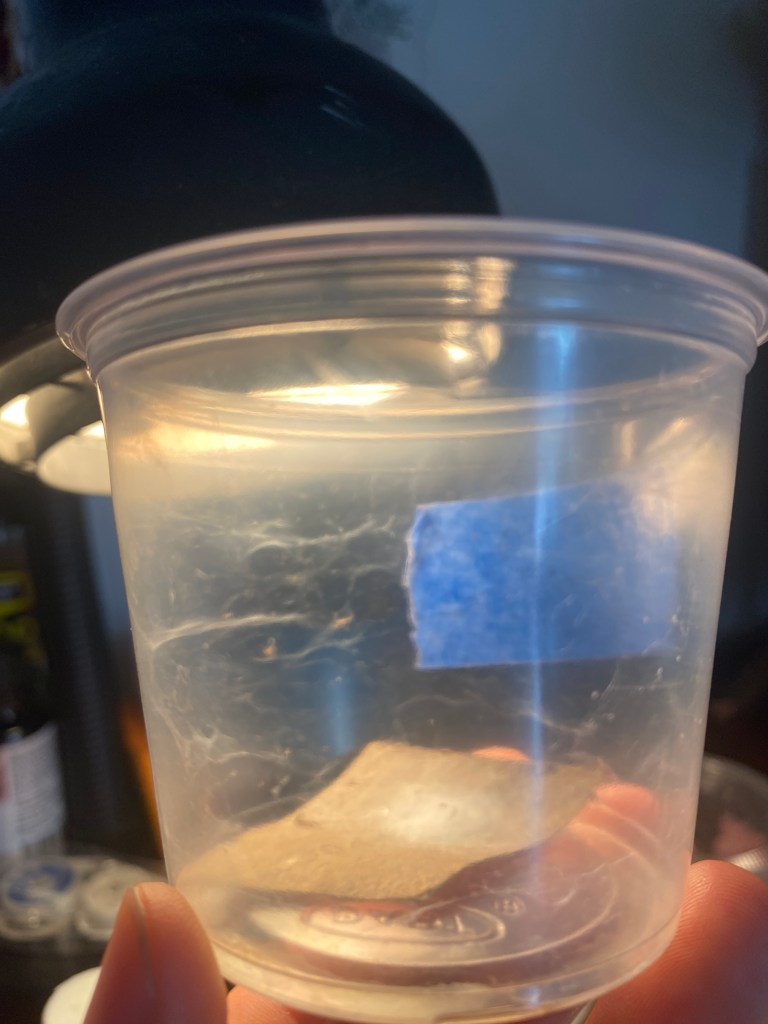

I captured the two pairs and put each “couple” in an enclosure. Funnel webs were built. I’m assuming that both male and female laid down some silk. Each made their own retreat funnel. They lived together peacefully for weeks and seemed to stay our of each others way. There was some leg contact between them, but it looked like agonistic behavior rather than friendly, but both pairs tolerated each other. During feeding, both would attack, but the males would yield to the female. I did observe one of the males scavenging what was left of a cricket after the female had her fill. The females were the queens of their castles, so what was up with the basement living situation with the kings on the throne?

At this time, I was keeping a female barn spider I saved from a friend’s garbage can. I caught a male from the basement (unlimited supply) and introduced him into her enclosure. He fumbled onto her web and stopped, but that was enough to get her attention. She ran at him in full attack mode and the poor guy ran in circles to get away! I removed him unharmed, but it was definitely not an amicable encounter and he definitely didn’t try to take over.

I could not find anything in the literature mentioning any kind of web takeover behavior. I did find some info that the male and female will peacefully cohabit webs during mating season, and that was evident with the couples that I found together. I didn’t try to introduce the male from one web into another or see what would happen if I put the males into the same web. I didn’t try to remove and introduce either of the females into the other web, either. I figured it’d be a bad situation.

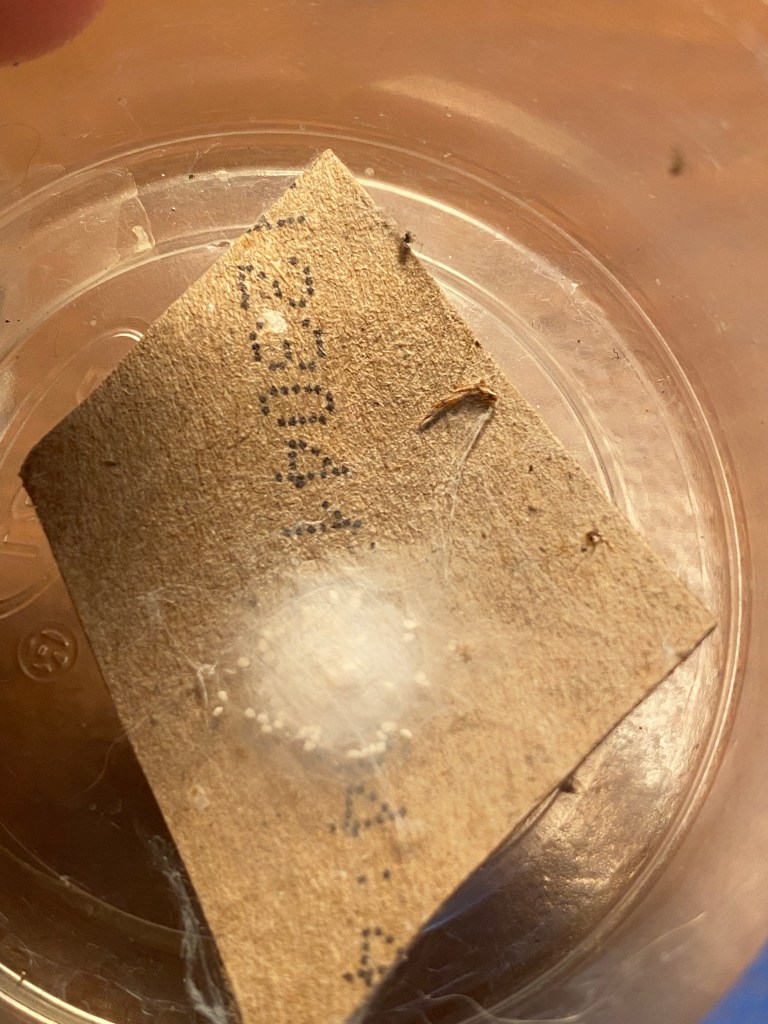

As it goes with the ways of nature, egg sacs appeared. I did not witness any mating. I’m sure I missed a lot since these guys are nocturnal and I’m not. Obviously something happened because, the eggs were viable, and soon, tiny little barn weavers were running around the enclosures making mini funnel webs.

The life expectancy of a female barn funnel weaver can be up to four years. Males lives are shorter. Typically, spiders last a season or two, but living inside houses allows them protection from predators and the elements, so they can live even longer. Unfortunately, and oddly, both of the female spiders I caught died before the males did. Maybe they were both older females? I have more questions than answers, but this is what keeps me so interested in spiders!

Barn funnel weavers have been in my basement windows forever, always there. I’ve done a million loads of laundry right in front of one of their window condos (there’s seven of them living in just that window) and I’ve never noticed anything exciting. I’ve identified them from friend’s houses and would be like, “Sigh…it’s only a barn funnel weaver. They’re very common”. Now, I’m quite interested in their habits and am looking forward to gaining more insight by paying more attention to the basement population. I’d like to end with this quote which I think complements this story well:

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

― Marcel Proust

If anyone has any similar observations or a lead to Tegenaria domestica’s everyday behavior, please share!

References:

Jacobs, Steve. Barn Funnel Weaver Spider. Penn State Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/barn-funnel-weaver-spider. November 18, 2022. Accessed August 2, 2023.

Kaston, B. J. (1948). Spiders of Connecticut. Bulletin of the Connecticut State Geological and Natural History Survey 70: 278-280.

Roth, V. D. (1968). The spider genus Tegenaria in the Western Hemisphere (Agelenidae). American Museum Novitates 2323: 1-33.

Ubick, D., Paquin, P., Cushing, P.E. and Roth, V. (eds). 2017. Spiders of North America: an identification manual, 2nd Edition. American Arachnological Society, Keene, New Hampshire, USA.

World Spider Catalog (2023). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 24.5 accessed Aug. 2023.

Leave a comment