Hazelwood Green is an urban brownfield that sits between the north shore of the Monongahela River and Irvine Street about 4 miles southeast of downtown Pittsburgh. Its 178-acres have been revitalized while preserving relics from the area’s steel industry. The roads and sidewalks have been built complete with trees and ornamental grasses, but most of the area has been leveled into lots awaiting development. The new sidewalks butt up against the vast vacant lots that are teeming with wildflowers and weeds. It’s the perfect habitat for wolf spiders.

My story starts here in autumn – Sept. 20, 2023. On this outing, I was specifically looking for wolf spiders for an upcoming program about nocturnal animals. I wanted to highlight the way wolf spider eyes glow in the dark if you hit them at the correct angle with a flashlight. Their eyes reflect light like cats. It really works! I was using this technique to find them.

I threw my field bag over my shoulder and disappeared off into the shadows tiptoeing along the edge of the sidewalk just beyond the glow of the Plaza lights. I held the flashlight from my hip so it would be at a more direct angle to any spiders on the ground. My light revealed isopods, crickets, and resting grasshoppers, but no shiny-eyed spiders. After about ten minutes of searching, I caught a shimmer! A wolf spider was under a bench about four feet away. As soon as I moved in for the capture, it disappeared into a crack in the cement. Feeling like this was my only wolf spider catching opportunity, I grabbed a long sprig of grass to try and tease it out. The spider had retreated into a dead end. I could just see the tips of its legs moving toward the opening with each tease, but then the spider would dart back into the crevice at the last minute. After a few tries, I was finally able to get the spider all the way out and scoop it up into a container.

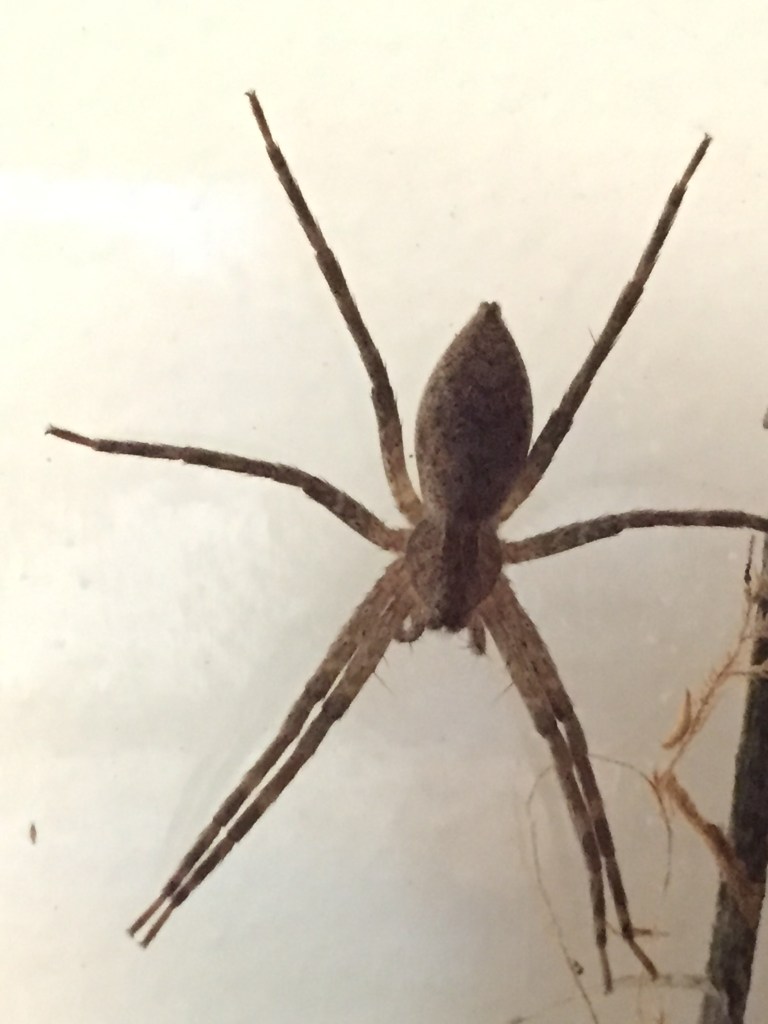

Feeling accomplished, I walked back into the light and held up the container for a closer look at who I had. It was definitely a wolf spider (Lycosidae family). You can tell by how the eyes are arranged. Some spiders that are often mistaken for wolf spiders are fishing spiders and funnel weavers, but only wolf spiders have a face like that!

As is the way when looking for spiders, I really didn’t have to go that far or look as long as I did because back at my car, almost RIGHT NEXT to it, were TWO wolf spiders totally exposed on the sidewalk. Of course! I was able to capture them much easier since there were no cracks for the spiders to dart into. Both of these spiders were much larger than the one I caught by the bench. I wasn’t sure which kind of wolf spiders I had, so I kept all three for identification and to use for the upcoming program at the end of October.

Let’s get a bit more into what a wolf spider is. The wolf spider family, Lycosidae, contains about 220 different species just in North America (over two thousand world-wide). They all of the same eye arrangement and body shape. All female wolf spiders carry their egg sacs around attached by silk to their spinnerets. When the eggs inside of the sac hatch and the spiderlings emerge, the wolf spider moms will carry them on their backs for a week or two. Most are nocturnal, although some species seem to like the daylight. They’re all hunters who will chase and tackle prey without the use of a capture web. They’re badass!

To a trained eye, there are subtleties in wolf spider markings and sizes that define one kind from the other. For instance, a lot of the smaller wolf spiders I find speeding through the grass during the day are in the Pardosa genus. Because the Hazelwood Green spiders were beefy, nocturnal, and lacked ring patterns on the legs, I guessed these wolf spiders were in the Tigrosa genus. Knowing what kind of spider you have (family, genus, and ultimately, species) gives you more insight into their natural histories and behaviors. Below are three different genera of wolf spiders revealing just a tiny snapshot of their diversity.

Once back at home with my three Hazelwood Green wolfies, I could see I had caught a mature female, named “Hazel” and a mature male, named “Woody”. Mature means they are fully grown with all of their male and female parts visibly developed and working. The one that gave me such a hard time under the bench was an immature spider (no visibly developed parts) and I wouldn’t be able to tell what sex it was until it molted again. I named that one “Bench”. Hazel, head to butt, was about twenty millimeters and Woody, although leggier, was smaller at about twelve millimeters. Bench was more like around nine millimeters.

Of course, having a mature male and female means there was the possibility that they would mate if they are the same species. About a week later, when everyone was established into a plush, predator-free terrarium (separate quarters, of course – spiders are cannibalistic), I introduced Woody into Hazel’s terrarium. As soon as Woody hit Hazel’s pheromone-laden silk trail, he began his courtship routine. Remember that wolf spiders are active hunters that do not make capture webs (there is one kind that does though, not these guys). They still use silk for many other purposes – a silken hiding spot for their down time, egg sacs, and trailing silk which carries chemical info for other wolf spiders who may cross their paths.

Woody was about two inches from Hazel who was hiding in a piece of tree bark. He began tapping his palps and shakily sticking his front legs out until they were almost straight. He was moving very slowly; cautiously. Suddenly, Hazel popped out of her hide and met him face to face! They were only half an inch apart! Woody slowly approached and I held my breath…will she attack or will she mate? Neither. Hazel darted to the other side of the terrarium as if she realized she was late for something.

Not really catching the drift, Woody continued to walk around slowly, tapping his palps, raising and lowering his body, stretching and tapping his front legs. I think I saw his abdomen vibrate but it wasn’t audible. Woody eventually circled around to Hazel and approached again, this time taking a few quick steps. Again, Hazel ran away. After about twenty minutes of Spider TV, I removed Woody. Hazel wasn’t interested. Maybe they weren’t the same species as I assumed. I tried two more times over the next few weeks, all with the same result.

In December, Bench, the immature wolf who had given me such a hard time, molted into a gorgeous male. His patterns were so pretty! I suspected he was the same species as Woody – they looked similar. I had not yet ID’d them to know for sure which was the main reason I decided to keep them all. It was a great opportunity to watch their growth and behavior.

Notice I said, December. In Pittsburgh, wolf spiders should be overwintering under leaves or stones to wait out of the cold. Since the wolf spiders of Hazelwood Green were now in a heated home (68 degrees), the spiders just kept living like there wasn’t a break. They would hide during the day under tree bark strips and come out at night in search of food, which was crickets. Bench really shouldn’t have molted into maturity this early. Being indoors affected his circadian rhythm. In the chilly, weeded lots of Hazelwood Green, there would not be any active females to mate with if he had gone out to mingle. Woody, the older male, began to slow down and stopped eating despite the warmth and regular meal accommodations. Since he was a mature male when I caught him in autumn, he naturally would not have lasted the winter. Having him inside may have given him an extra week or two but he was getting to the end of his life cycle. Woody lasted until late winter (a long time) and called it quits. Bench also crossed the rainbow bridge around that time. The boys don’t live that long.

Hazel, on the other hand, was ready to go! Female wolf spiders can overwinter as adults and can have two breeding seasons. Again, her posh, heated home had thrown off her circadian rhythm. I found her with an egg sac in January. She had to have already been mated before I caught her because her monitored encounters with ‘ole Woody never lead to anything. Wolf spiders can store sperm and produce multiple egg sacs from one mating. I assume that’s what happened.

Unfortunately, Hazel discarded the egg sac. She had been carrying it around for what seemed like over a month. If the sac were filled with fertile eggs, I should’ve seen some cutie patootie lil wolfies after about three to four weeks! Lo and behold, she produced another egg sac in April. I would see her sitting outside of her retreat with her sac in the sunshine. She was being a good mom. But again, for unknown reasons, that sac was also abandoned. I was sad! This poor mama kept trying and trying! I kept both sacs and no parasites emerged from either of them. I didn’t know what was wrong.

Hazel was not done. In late May, she had produced a THIRD sac and this time it was fertile! In June of 2023, Hazel had a whole bunch of spiderlings all over her back! I was thrilled!

Hazel carried her spiderlings around on her back for about two weeks. They gradually crawled off on their own and started independent lives around the enclosure. They were so small and cryptic I lost track of many of them. I’m sure they were eating each other in addition to fruit flies and the baby crickets I didn’t realize I was raising…a gravid cricket must’ve laid some eggs in there before she became dinner. Wolf spiderlings are fierce! They will tackle prey twice their size! I watched one pounce on a cricket and hold on like a cowboy at a rodeo while the cricket jumped all around! Wolf spiders will flip upside down, grab bugs in the air, and give chase. They are SO fun to watch! Here’s a video of some highlights!

I kept six of the spiderlings and released the others back to Hazelwood Green. Of those six, four have survived. At this point, they are eight months old and nearly the size of their mom. Hazel died after her second program about eyeshine in October 2023. It was the very same program we did the first year I found her. I was sad. She was so cool.

I was finally able to properly ID the spiders. Bench, Hazel, and Woody were all the same species – Tigrosa helluo. These are harmless, common wolf spiders found all around Western PA. They can be found in meadows, the woods, gardens, and your yard. Maybe even in your house by accident. For most of you, identifying the totally buff, brown spider that just appeared out of nowhere as a wolf spider is awesome enough at a distance. For you arachnophiles who love to get a closer look, T. helluo can be identified by its size, spotted belly, and plain legs (no stripes). If you are able to see the underneath, maybe if you catch it in a clear-bottomed container, the sternum and first leg segments (coxae) are black. Also note the tan line that runs from between the eyes all the way back to the abdomen. It can get tricky – the best way to confirm is to dissect the genitalia…I know, but that’s how it’s done unless you can extract a DNA sample.

It has been super fun to observe and learn more about these cool spiders! As the development in the Hazelwood area continues, I hope the wolf spiders are able to hide in the cracks under benches and persist through the chaos. Especially Hazel’s kin! These spiders are a sign of a thriving ecosystem that has bloomed out of the rust of our city’s bygone steel era. Long live the wolf spiders of Hazelwood Green!

Benson, K., & Suter, R. B. (2013). Reflections on the tapetum lucidum and eyeshine in lycosoid spiders. The Journal of Arachnology, 41(1), 43–52.

Brady, A. R. (2012). Nearctic species of the new genus Tigrosa (Araneae: Lycosidae). Journal of Arachnology 40(2): 182-208.

Dondale, C. D. & Redner, J. H. (1990). The insects and arachnids of Canada, Part 17. The wolf spiders, nurseryweb spiders, and lynx spiders of Canada and Alaska, Araneae: Lycosidae, Pisauridae, and Oxyopidae. Research Branch Agriculture Canada Publication 1856: 1-383.

Kaston, B.J. 1936. The senses involved in the courtship of some vagabond spiders. Entomol.

Americana, 16:97-167.

Kaston, B. J. (1948). Spiders of Connecticut. Bulletin of the Connecticut State Geological and Natural History Survey 70: 1-874.

Ubick, D., Paquin, P., Cushing, P.E. and Roth, V. (eds). 2017. Spiders of North America: an identification manual, 2nd Edition. American Arachnological Society, Keene, New Hampshire, USA.

So many people cite the jumpers (family Salticidae) as the “entry” spider, or “spark” spider for budding arachnologists. I think seeing eye-shines of wolf spiders is an equally frequent spark for folks who attend nocturnal “spider walks” that I’ve attended. There is something seemingly magical about being able to see, even a very small, wolf spider in the lawn at night, sometimes many yards ahead. Thanks for this nice story.

LikeLike